By David Labby, MD, PhD, Health Share of Oregon

It is now a truism that the world will not be the same after the COVID-19 pandemic. What will this mean for the most vulnerable, medically and socially complex members of our communities and the programs that serve them? What could complex care look like in the “new normal?”

There will definitely be more need, especially in low-income communities. Coronavirus is a disparities risk multiplier. Job loss, housing and food instability, social isolation, increased interpersonal violence, and abuse and neglect all increase the risk of destabilization for those already struggling with complex medical and social challenges, on the edge, or even in stable recovery. Will those marginalized groups paying the greatest price for the pandemic get the help they need?

There are increasing concerns that health care systems will experience revenue losses and be forced to implement program closures not just in physical health, but also in the already underfunded but critical mental health and substance use treatment systems. The non-profit social safety net is also at risk, with local and culturally-specific organizations facing increased demand, but unable to hold their usual fundraising events.

Recent Studies Inform the Gaps of Complex Care

Just before the pandemic, a study from the Camden Coalition brought into sharp focus both the importance of community resources for complex care success and the limitations of episodic interventions. The long-awaited randomized controlled trial of the Camden Coalition’s core intervention found no difference in rehospitalization rates between individuals provided short-term care management after discharge and those who were not. Their conclusions illuminate two major challenges facing complex care stakeholders: (1) Care management alone cannot be expected to address lifetimes of complexity; and, equally important, (2) Community resources, or the lack of them, are critical determinants of patient stabilization.

These takeaways likely resonate with many in the field. Medical complexity in communities experiencing poverty and marginalization is too frequently associated with lifelong pathways of adversity. A recent study of medically complex and high-cost Medicaid members in Oregon showed that high percentages of this population experienced adverse life events: 62 percent experienced homelessness, 63 percent have or had a substance use disorder (SUD), 52 percent have been incarcerated, and 50 percent endured adult physical abuse. Notably, a high percentage experienced early life adversity, including 56 percent with four or more adverse childhood experiences, 32 percent homelessness as a child, and 40 percent early substance use. These medically complex Medicaid members in Oregon had 8-10 fold higher rates of behavioral and physical comorbidities than medically low-risk members; and medically complex high acute care utilizers were averaging close to $50,000 per year in costs.

Not unexpectedly, cross-sector data analysis shows that complex patients also tend to be high utilizers of multiple systems, such as health care, criminal justice, housing services, and behavioral health.

The Basis for Recovery-Oriented Complex Care

As the Camden study suggests, medically and socially complex individuals in vulnerable communities need more resources for longer periods, with the goal of sustaining “recovery” as their overarching health-related social need. Such an approach could resemble the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) Recovery-Oriented Systems of Care (ROSC) for individuals with mental health conditions and/or SUDs.

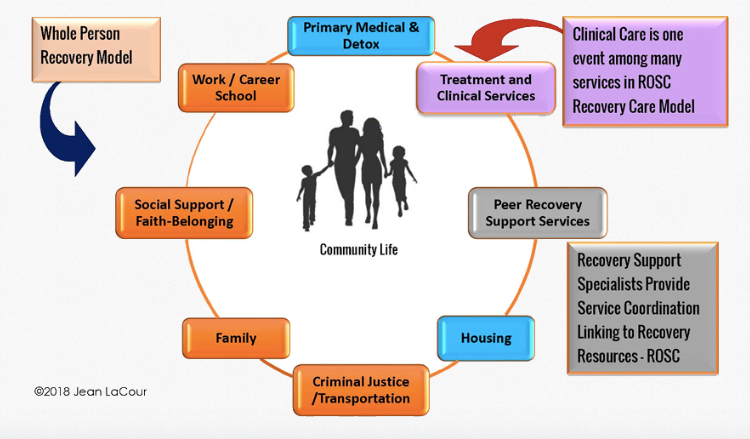

The ROSC model (see Figure 1) was developed from the need to move beyond the professionally directed, acute care treatment approach of the medical model. In the ROSC model, medical treatment is but one part of recovery. Long-term stable recovery is promoted through networks of formal and informal services, which include non-health care services that foster new personal and community relationships while reinforcing individual strengths, goals, and resilience. Culturally-specific organizations, peers, and community health workers play key roles in establishing the individual’s supportive “ecosystem” over time.

Figure 1. Recovery-Oriented System of Care (ROSC): Support for the Whole Person

Source: Dr. Jean LaCour, 2018. Net Institute. ©

The Road to Recovery-Oriented Complex Care

As the pandemic response shifts from crisis to ongoing management, the work done to mitigate COVID-19 presents key opportunities for building the new relationships, skills, and capacities needed for a recovery-oriented approach to complex care. Here are some initial possibilities:

- Building and maintaining safety net ecosystems through cross-sector partnerships. The pandemic is making communities acutely aware of their limited ability to respond to multiple social needs such as housing, food security, or crisis support. These are all needs that have long been present, particularly among the most vulnerable. Current emergency response efforts for vulnerable populations, such as temporary homeless shelters and isolation hotels or early releases from incarceration to control viral spread, will need to move to much longer term sustainable strategies, covering many months if not years. Primary care providers will also be looking to address the social needs of their patients.

The pandemic is already strengthening cross-system partnerships to expand safe shelter, food assistance, and other social services in communities across the country, such as King County, Washington and New York City. As these activities spread over the coming months, they could become ongoing efforts for resource coordination, investment, and development. Health care leaders committed to addressing complex needs can not only engage in the community response, but can also help provide the leadership required for sustained efforts to build the robust safety net services that are critical to those they serve.

- Empowering vulnerable communities. The racial and ethnic disparities of COVID-19 incidence mean that effective initiatives to manage the pandemic will need to be community based and culturally specific. Enabling community-based organizations (CBOs) to lead mitigation efforts for those they serve can help build their capacity to support those at risk. This could lead to high-value partnerships between CBOs and health systems, including future ROSC partnerships with complex care programs focused on individual long-term recovery support.

- Identifying social risk and supporting long-term recovery. Most health systems are doing some form of telephonic outreach to ensure that those with high COVID-19 mortality risk have the supports they need to stay safely at home. New assessment tools are being developed. Different staffing approaches – from care managers to medical assistants and community health workers – are being tested. Infection risk is predicted to increase as states relax stay-at-home orders, so social risk screening outreach to high-risk individuals may best be ongoing, unlike time-limited care management. As health systems figure out how to most effectively conduct ongoing social risk outreach, whether based in primary care or in health systems or plans, they will create monitoring tools and workflows that could also be used to longitudinally support those in recovery and their formal and informal systems of care.

- Re-contracting with primary care. The pandemic-driven adoption of widespread telehealth is undoubtedly changing primary care. Still, there is increasing recognition that new payment models will be needed not just to maintain the shift to virtual care, but also to ensure the financial viability of many practices. Payers and providers will need to negotiate payment, opening further potential to move away from fee-for-service toward rewarding value over volume, including global payments with risk-adjusted monthly fix fee capitation.

The job losses, disruption of social supports, and predicted mental health crisis from COVID-19 will also require primary care practices to address increasing levels of social need, depression and anxiety, and substance use even as they adapt to new virtual care platforms. As practices reopen with less need to staff face-to-face visits, some will look to use their new capacity to expand services in areas of previous primary care interest that are now clearly aligned with pandemic response: addressing health-related social needs, integrating behavioral health, and, more recently, introducing addiction medicine through medication assisted treatment.

When the pandemic brings payers and providers to the table to renegotiate payment, they have the opportunity to promote an advanced primary care practice with teams that include care managers, behaviorists, community health workers, and others needed for a more effective holistic approach to care, provided both virtually and face-to-face. This, after all, is what many have long wanted for primary care. In addition, this has been the direction of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) demonstration project. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is perhaps in the best position as part of the pandemic response.

What does this mean for complex care? The more these primary care capacities are developed, the more relevant a recovery orientation becomes. With payer support, such advanced primary care clinics could become key partners in the network of services mobilized to sustain long-term recovery.

A Nation in Recovery

It is impossible to know where the pandemic will lead health care. Some primary care clinics are already looking to participate in the next phase of COVID-19 surveillance and follow-up, potentially beginning a long hoped for partnership with public health.

Perhaps most importantly, when the ravages of the pandemic finally end, “recovery” will likely take on a different meaning in our national dialogue. We will be a nation in recovery, all called upon to support recovery efforts and build recovery-oriented systems. For the field of complex care, this will mean ensuring that those whose lives, health, and communities have been most disrupted are provided the resources they need for their own full recovery. We have the opportunity to start building toward that goal even as we work to solve the challenges of the current moment.